Scroll to:

Genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents and delayed stroke development in vertebral artery dissection: a clinical case

https://doi.org/10.37489/2588-0527-2025-2-46-52

EDN: JUZAMW

Abstract

A clinical case of a 35-year-old man with dissection of the left vertebral artery is presented, in connection with which dual antiplatelet therapy in the form of aspirin and clopidogrel, as well as anticoagulant therapy with enoxaparin, was prescribed to prevent the development of thromboembolic complications.

On day 5, the patient developed numbness in the right extremities, dysphagia and dysarthria, increased ataxia, left-sided ptosis, right-sided hemiparesis and hemihypesthesia. A control MRI scan of the brain revealed a focus of ischemia in the medulla oblongata. Pharmacogenetic testing was performed with the study of genetic resistance to antiplatelet drugs with the determination of polymorphic variants rs4244285*2, rs4986893*3, rs12248560*17 of the CYP2C19 gene. It was revealed that the patient was a carrier of the CT genotype according to the rs12248560 polymorphic variant, the GA genotype according to the rs4244285 polymorphic variant, and the GG genotype according to the rs4986893 polymorphic variant of the CYP2C19 gene. This corresponds to a variant of an intermediate metabolizer with an indistinctly defined effect of clopidogrel. The above clinical observation with the development of delayed ischemic stroke after spinal artery dissection (DPA) draws attention to the problem of genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents in this patient population. The development of delayed ischemic stroke in DPA is the basis for determining genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents and the subsequent possible change in treatment tactics.

Keywords

For citations:

Popugaev K.A., Kvasnikov A.M., Karpova O.V., Sysoeva A.A., Kruglyakov N.M., Markhulia D.S., Popugaeva O.K. Genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents and delayed stroke development in vertebral artery dissection: a clinical case. Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics. 2025;(2):46-52. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.37489/2588-0527-2025-2-46-52. EDN: JUZAMW

Introduction

Vertebral artery dissection (VAD) is defined as the penetration of blood from the vertebral artery (VA) lumen through a damaged intimal layer into the vessel wall, with subsequent propagation of blood between the arterial layers [1]. VAD can be either spontaneous or traumatic [2]. The clinical presentation of VAD ranges from an asymptomatic course to severe stroke and even fatal outcomes due to complete arterial rupture [3]. However, the most frequent clinical manifestations of VAD in the acute phase are cephalalgia, neck pain, and dizziness [4]. Given the potential for non-traumatic VAD to present with an absence of clinical symptoms, its precise incidence remains unknown. Nevertheless, within the population of trauma patients, who typically undergo a diagnostic workup sufficient to detect VAD, this pathology is identified in 70–77% of patients with cervical spine fractures and in approximately 20% of victims with traumatic brain injury (TBI) [5, 6]. VAD most frequently occurs in individuals who have experienced falls and road traffic accidents [7].

In 1999, the Denver classification of VAD was proposed, based on the morphological characteristics of the arterial injury (Table 1) [8].

Table 1. Denver Classification of Vertebral Artery Dissection

| Grade | Morphological Characteristics |

|---|---|

| I | Dissection with less than 25% luminal stenosis |

| II | Dissection/intramural hematoma with more than 25% luminal stenosis, with intraluminal thrombosis or intimal flap |

| III | Pseudoaneurysm |

| IV | Vessel occlusion |

| V | Transection |

The incidence of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) secondary to VAD is reported by various authors to range from 5% to 24%, with these rates increasing with higher grades of dissection severity [6, 9]. Stroke resulting from VAD can occur not only in the hyperacute phase but also in a delayed manner [10]. The established causes of delayed ischemic stroke in patients with VAD are arterio-arterial thromboembolism and the progression of VA thrombosis with an increase in its extent [11].

A cornerstone in the management of patients with VAD, including for the secondary prevention of delayed stroke, is the timely administration of adequate antiplatelet therapy [12]. Theoretically, genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents could be one potential cause of delayed ischemic stroke in patients with VAD. However, a review of the available literature revealed no data addressing this issue. This clinical case report describes a patient with VAD and genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents.

Clinical Case

A 35-year-old male patient (Mr. Ch.) experienced a sudden onset of severe cephalalgia and neck pain during a sharp turn of his head while driving. The patient self-administered non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and sought medical attention only on the third day, after the onset of dizziness and intensification of neck pain. He was admitted to the A.I. Burnazyan Federal Medical and Biophysical Center with a referral diagnosis of "Vertebrobasilar arterial system syndrome."

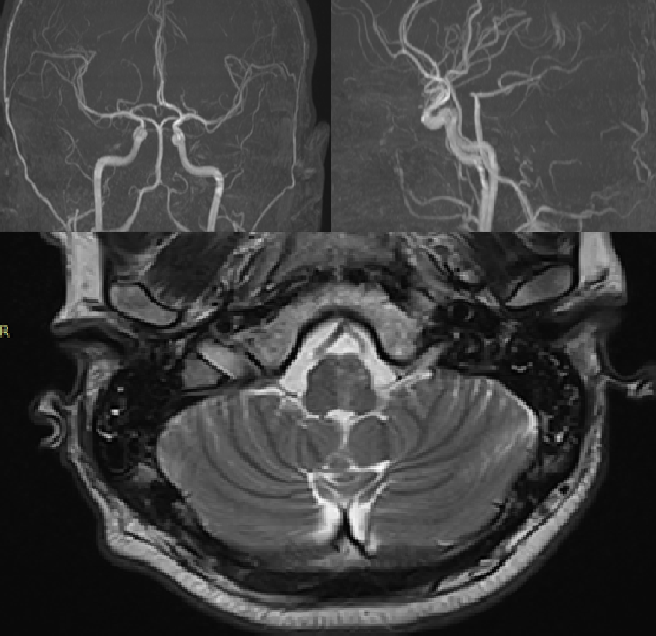

Upon admission, the patient was conscious but presented with cerebellar dysarthria and vestibulo-atactic syndrome. No other focal neurological deficits were detected. Doppler ultrasound of the major neck vessels revealed a dissection of the left vertebral artery. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain confirmed a dissection in the V4 segment of the left vertebral artery. No cerebral ischemic foci were identified (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Dopplerography of the main vessels of the neck.

No indications for surgical intervention were present. Pathogenetic dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with acetylsalicylic acid (100 mg) and clopidogrel (75 mg) was initiated, alongside anticoagulant therapy with enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolic complications. The patient was managed in the neuro-intensive care unit for two days and was subsequently transferred to the neurology department in a stable condition.

On the 5th day of hospitalization in the neurology department, the patient's blood pressure increased to 190/100 mm Hg. He developed numbness in the right limbs, dysphagia, dysarthria, worsening ataxia, left-sided ptosis, and right-sided hemiparesis and hemihypoesthesia. A follow-up MRI of the brain revealed an ischemic focus in the medulla oblongata (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. MRI examination of the brain.

The patient was transferred back to the intensive care unit. Pharmacogenetic testing was performed using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to investigate genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents by determining the polymorphic variants rs4244285*2, rs4986893*3, and rs12248560*17 of the CYP2C19 gene. The analysis revealed that the patient was a carrier of the CT genotype for polymorphic variant rs12248560, the GA genotype for rs4244285, and the GG genotype for rs4986893 of the CYP2C19 gene. This genotype corresponds to an intermediate metabolizer phenotype with an uncertain response to clopidogrel. A correction of the antiplatelet therapy was deemed necessary. Clopidogrel was replaced with prasugrel at a maintenance dose of 10 mg, with the decision to forgo a loading dose. Therapy with aspirin in combination with prasugrel, as well as prophylactic anticoagulation with enoxaparin, was continued.

Over the next three days, no progression of neurological symptoms was observed, hemodynamics stabilized, and the patient was transferred back to the neurology department. Over the subsequent two weeks, the focal neurological symptoms regressed, and the patient was discharged from the hospital in a satisfactory condition.

Discussion

This case is unique as it illustrates an association between genetic resistance to clopidogrel and the development of delayed ischemic stroke in a patient with VAD. Although VAD is a common cause of stroke in the posterior cerebral circulation, this pathology receives insufficient attention from clinicians and in terms of the quantity and quality of research dedicated to it. Consequently, the pathogenesis of stroke in VAD remains poorly understood in many aspects, particularly concerning delayed stroke. While AIS in the hyperacute phase of VAD typically results from severe VA injury and subsequent cessation of blood flow [13], its occurrence likely requires additional anatomical risk factors, such as hypoplasia of the contralateral VA, an incomplete circle of Willis, underdeveloped cerebral arterial anastomoses, or severe atherosclerosis of cerebral arteries [15]. In any case, the pathogenesis of hyperacute stroke in VAD is relatively clear, which cannot be said for delayed stroke.

According to the literature, delayed stroke in VAD is attributed to either arterio-arterial embolism or the propagation of thrombosis [16]. An increase in the size of the intramural hematoma, the dissected area, or the zone of detached intima can lead to the extension of VA thrombosis. Currently, there are limited technical means to prevent these complications [17]. The administration of dual antiplatelet therapy is fundamental in preventing both arterio-arterial embolism and the extension of thrombosis [18].

The first-line drugs for DAPT in VAD are a combination of acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel [19]. In some clinical situations, adequate suppression of platelet reactivity is not achieved, which may be due to impaired absorption, distribution, metabolism, or elimination of the antiplatelet agents [20]. While altered absorption, distribution, and elimination are more characteristic of critically ill patients, impaired metabolism of antiplatelet agents can occur in any patient, regardless of their condition, due to genetic polymorphisms causing genetic resistance [20].

The prevalence of genetic resistance to acetylsalicylic acid ranges from 5% to 45%, and to clopidogrel from 20% to 45% [21]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms involving COX-1, COX-2, and other platelet-related genes can alter the antiplatelet effect of acetylsalicylic acid [22]. Resistance to clopidogrel is primarily associated with polymorphic variants of the CYP2C19 gene [14]. The CYP2C19 gene, part of the cytochrome P450 family, is involved in the bioactivation of clopidogrel [23]. Carriers of the rs4244285 and rs4986893 alleles of the CYP2C19 gene often fail to achieve adequate platelet inhibition [23]. Conversely, the presence of the rs12248560 allele of the CYP2C19 gene enhances the metabolism of clopidogrel and increases the risk of bleeding.

Currently, there are no specific guidelines regarding the testing for genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents in patients with VAD. The routine use of genetic analysis is likely not feasible. However, given the high risk of delayed stroke in VAD, it is prudent to search for reliable laboratory markers, routinely used in clinical practice, that could help suspect genetic resistance. In the population of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the CT-EXTEM parameter in rotational thromboelastometry has been proposed as such a marker [24]. In this context, further research is needed to identify similar criteria for VAD patients.

Aspirin is an inhibitor of COX-1 and COX-2, while clopidogrel is a P2Y12 receptor antagonist [25]. For patients with VAD, there may be little clinically justified rationale for testing genetic resistance to acetylsalicylic acid, as there are currently no viable alternatives. In contrast, testing for genetic resistance to clopidogrel is highly significant. If resistance is identified, the dose of clopidogrel should be increased or it should be replaced with another P2Y12 receptor antagonist. Convincing evidence exists linking the CYP2C19 genotype to clinical outcomes in patients with ischemic stroke. Results from a large meta-analysis demonstrated that carriers of the CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele undergoing DAPT with clopidogrel for transient ischemic attack have a significantly higher risk of stroke, and stroke patients have a higher risk of recurrent stroke, compared to non-carriers [26].

Prasugrel and ticagrelor are P2Y12 receptor antagonists that serve as alternatives to clopidogrel [27]. Unlike clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor have a significantly lower prevalence of genetic resistance in the population; it is described in 3–15% of patients for prasugrel and 0–3% for ticagrelor [27]. This is due to differences in the metabolism of these antiplatelet agents [28]. Therefore, in cases of VAD with confirmed genetic resistance to clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor should be considered as alternative P2Y12 antagonists.

Some authors suggest that for patients with a heterozygous genotype for rs4244285 in the CYP2C19 gene (leading to a non-functional enzyme) combined with a heterozygous genotype for rs12248560, doubling the clopidogrel dose to 150 mg daily may overcome resistance [29]. However, in our view and that of other leading experts, this strategy is unlikely to successfully overcome genetic resistance and may expose patients with VAD to the risk of delayed stroke [30]. The presented clinical case demonstrates the safety and efficacy of a treatment strategy for VAD that involved continuing antiplatelet therapy with the substitution of clopidogrel for prasugrel.

Conclusion

This clinical case of a patient who developed a delayed ischemic stroke following VAD highlights the issue of genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents in this patient population. The occurrence of a delayed ischemic stroke in the context of VAD warrants consideration for testing genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents and subsequent potential modification of the treatment regimen. Further research is necessary to establish criteria for initiating diagnostics for genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents and to develop an effective protocol for adjusting antiplatelet therapy in patients with VAD.

References

1. Kalashnikova LA, Dobrynina LA. Dissection of cerebral arteries: ischemic stroke and other disorders. Moscow: Publishing House "Vako", 2013. (In Russ.). ISBN 978-5-408-01143-8.

2. Kalashnikova LA. Dissection of cervico-cerebral arteries and cerebrovascular disease. Annals of Clinical and Experimental Neurology. 2007;1(1):41-49. (In Russ.)].

3. Yarikov AV, Logutov, AO, Muravina, EA, et al. Dissection of Brachiocephalic and Intracranial Arteries: Etiology, Clinic, Diagnosis and Treatment. Bulletin of Science and Practice. 2023;9(5):235-256. (In Russ.). doi: 10.33619/24142948/90/32.

4. Gubanova MV, Kalashnikova LA, Dobrynina LA, et al. Isolated headache and cervical pain in dissection of both internal carotid arteries (clinical case). Astrakhan Medical Journal. 2019;1:108-115. (In Russ.). doi: 10.17021/2019.14.1.108.115.

5. Biffl WL, Moore EE, Elliott JP, et al. The devastating potential of blunt vertebral arterial injuries. Ann Surg. 2000 May;231(5):672-81. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200005000-00007.

6. Fassett DR, Dailey AT, Vaccaro AR. Vertebral artery injuries associated with cervical spine injuries: a review of the literature. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008 Jun;21(4):252-8. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3180cab162.

7. Temperley HC, McDonnell JM, O'Sullivan NJ, et al. The Incidence, Characteristics and Outcomes of Vertebral Artery Injury Associated with Cervical Spine Trauma: A Systematic Review. Global Spine J. 2023 May;13(4):1134-1152. doi: 10.1177/21925682221137823.

8. Biffl WL, Moore EE, Offner PJ, et al. Optimizing screening for blunt cerebrovascular injuries. Am J Surg. 1999 Dec;178(6):517-22. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00245-7.

9. Lebl DR, Bono CM, Velmahos G, et al. Vertebral artery injury associated with blunt cervical spine trauma: a multivariate regression analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 Jul 15;38(16):1352-61. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318294bacb.

10. Lichy C, Metso A, Pezzini A, et al.; Cervical Artery Dissection and Ischemic Stroke Patients-Study Group. Predictors of delayed stroke in patients with cervical artery dissection. Int J Stroke. 2015 Apr;10(3):360-3. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00954.x.

11. Harrigan MR. Ischemic Stroke due to Blunt Traumatic Cerebrovascular Injury. Stroke. 2020 Jan;51(1):353-360. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026810.

12. Vankawala J, Yi Z, Koneru M, et al. Evaluating the Role of Imaging Markers in Predicting Stroke Risk and Guiding Management After Vertebral Artery Injury: A Retrospective Study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2025 Jun 3:ajnr. A8866. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A8866.

13. Teasdale B, Owolo E, Padmanaban V, et al. Traumatic Vertebral Artery Injury: Diagnosis, Natural History, and Key Considerations for Management. J Clin Med. 2025 May 2;14(9):3159. doi: 10.3390/jcm14093159.

14. Esposito EC, Kufera JA, Wolff TW, et al. Factors associated with stroke formation in blunt cerebrovascular injury: An EAST multicenter study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022 Feb 1;92(2):347-354. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003455.

15. Lee CR, Luzum JA, Sangkuhl K, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2C19 Genotype and Clopidogrel Therapy: 2022 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022 Nov;112(5): 959-967. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2526.

16. Scott WW, Sharp S, Figueroa SA, et al. Clinical and radiological outcomes following traumatic Grade 3 and 4 vertebral artery injuries: a 10-year retrospective analysis from a Level I trauma center. The Parkland Carotid and Vertebral Artery Injury Survey. J Neurosurg. 2015 May;122(5):1202-7. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.JNS1461.

17. Stein DM, Boswell S, Sliker CW, et al. Blunt cerebrovascular injuries: does treatment always matter? J Trauma. 2009 Jan;66(1):132-43; discussion 143-4. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318142d146.

18. Cothren CC, Biffl WL, Moore EE, et al. Treatment for blunt cerebrovascular injuries: equivalence of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents. Arch Surg. 2009 Jul;144(7):685-90. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.111.

19. Zeineddine HA, King N, Lewis CT, et al. Blunt Traumatic Vertebral Artery Injuries: Incidence, Therapeutic Management, and Outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2022 Apr 1;90(4):399-406. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001843.

20. Cargnin S, Ferrari F, Terrazzino S. Impact of CYP2C19 Genotype on Efficacy and Safety of Clopidogrel-based Antiplatelet Therapy in Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Patients: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Non-East Asian Studies. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2024 Dec;38(6):1397-1407. doi: 10.1007/s10557-023-07534-0.

21. Ivanov I, Cataldo M, Cocchiara A, Nguyen R. Vertebral Artery Dissection. BMJ Case Rep. 2024 Jan 9;17(1):e255923. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2023-255923

22. Kuzmina IM, Markhuliya DS, Popugaev KA, Kiselev KV. Antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndrome. Russian Sklifosovsky Journal of Emergency Medical Care. 2021;10(4):769-777. (In Russ.). doi: 10.23934/2223-9022-2021-10-4-769-777.

23. McDermott JH, Leach M, Sen D, et al. The role of CYP2C19 genotyping to guide antiplatelet therapy following ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2022 Jul;15(7):811-825. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2022.2108401

24. Markhulia DS, Popugaev KA, Petrikov SS, et al. The influence of genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents on clinical and laboratory parameters and outcomes in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Pharmateka. 2023;9/10:84-94. (In Russ.). doi: 10.18565/pharmateca.2023.9-10.84-94.

25. Sammut MA, Rahman MEF, Bridge C, et al. Pharmacodynamic effects of early aspirin withdrawal after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with ticagrelor or prasugrel. Platelets. 2025 Dec;36(1):2507037. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2025.2507037.

26. Pan Y, Chen W, Xu Y, et al. Genetic Polymorphisms and Clopidogrel Efficacy for Acute Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circulation. 2017 Jan 3;135(1):21-33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024913.

27. Laurent D, Dodd WS, Small C, et al. Ticagrelor resistance: a case series and algorithm for management of non-responders. J Neurointerv Surg. 2022 Feb;14(2):179-183. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017638.

28. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al; PLATO Investigators; Freij A, Thorsén M. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009 Sep 10;361(11):1045-57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327.

29. Harmsze AM, van Werkum JW, Ten Berg JM, et al. CYP2C19*2 and CYP2C9*3 alleles are associated with stent thrombosis: a case-control study. Eur Heart J. 2010 Dec;31(24):3046-53. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq321.

30. Minderhoud C, Otten LS, Hilkens PHE, et al. Increased frequency of CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles in clopidogrel-treated patients with recurrent cerebral ischemia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022 Jul;88(7):3335-3340. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15282.

About the Authors

K. A. PopugaevRussian Federation

Konstantin A. Popugaev — PhD, Dr. Sci. (Med.), Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Deputy Chief Physician for Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Head of the Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Department No. 3, State Research Center — Burnasyan Federal Medical Biophysical Center of Federal Biological Agency; Head of the Department of Anesthesiology, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care at the Medical and Biological University of Innovation and Continuing Education, State Research Center — Burnasyan Federal Medical Biophysical Center of Federal Biological Agency.

Moscow

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest

A. M. Kvasnikov

Russian Federation

Artem M. Kvasnikov — PhD, Cand. Sci. (Med), the anesthesiologist-resuscitator; Assistant of the Department of Anesthesiology, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care at the Medical and Biological University of Innovation and Continuing Education, State Research Center — Burnasyan Federal Medical Biophysical Center of Federal Biological Agency.

Moscow

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest

O. V. Karpova

Russian Federation

Olga V. Karpova — PhD, Cand. Sci. (Med), Head of the Neurology Department for the treatment and rehabilitation of patients with stroke and CNS diseases, Assistant Professor of the Department of Neurology with courses in neurosurgery, preventive medicine, and health-saving technologies, State Research Center — Burnasyan Federal Medical Biophysical Center of Federal Biological Agency.

Moscow

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest

A. A. Sysoeva

Russian Federation

Anya A. Sysoeva — Resident of the Department of Anesthesiology, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care at the Medical and Biological University of Innovation and Continuing Education, State Research Center — Burnasyan Federal Medical Biophysical Center of Federal Biological Agency.

Moscow

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest

N. M. Kruglyakov

Russian Federation

Nikolay M. Kruglyakov — Head of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Department No. 2, State Research Center — Burnasyan Federal Medical Biophysical Center of Federal Biological Agency; Assistant of the Department of Anesthesiology, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care at the Medical and Biological University of Innovation and Continuing Education, State Research Center — Burnasyan Federal Medical Biophysical Center of Federal Biological Agency.

Moscow

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest

D. S. Markhulia

Russian Federation

Dina S. Markhulia — PhD, Cand. Sci. (Med), anesthesiologistresuscitator at the intensive care unit for cardiac surgery patients, Sklifosovsky Institute.

Moscow

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest

O. K. Popugaeva

Russian Federation

Olga K. Popugaeva — 4th-year student of the Faculty of Pediatrics, I. M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University.

Moscow

Competing Interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest

What is already known on this topic?

Definition and Causes: Vertebral artery dissection (VAD) is a tear in the artery wall with an intramural hematoma. It can be spontaneous or traumatic.

Stroke Risk: VAD is a significant cause of ischemic stroke, particularly in young adults. The stroke can occur immediately or in a delayed fashion.

Stroke Mechanisms: The primary mechanisms are arterio-arterial embolism and the propagation of thrombosis within the damaged artery.

Standard Treatment: The cornerstone of conservative therapy and secondary stroke prevention is dual antiplatelet therapy (acetylsalicylic acid + clopidogrel).

Problem of Resistance: Genetic resistance to clopidogrel, associated with polymorphisms of the CYP2C19 gene, is a known factor that reduces its efficacy.

What does the article add?

- Unique Clinical Case: It provides the first detailed description of a link between confirmed genetic resistance to clopidogrel and the development of delayed ischemic stroke specifically in a patient with VAD, despite standard therapy.

Proof of Effective Therapy Adjustment: Using a practical example, it demonstrates that replacing clopidogrel with prasugrel (which is less susceptible to genetic resistance) in such a patient is a safe and effective strategy, leading to stabilization and regression of symptoms.

Highlighting the Issue for VAD: The article emphasizes that the problem of genetic resistance to antiplatelets in VAD is understudied and requires more attention.

How might this affect clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

- Changing Approach to "Breakthrough" Strokes: The occurrence of a stroke in a VAD patient while on standard antiplatelet therapy may become an indication for testing for genetic resistance to clopidogrel.

Therapy Personalization: If resistance is identified, practice may shift towards early replacement of clopidogrel with alternative drugs (prasugrel, ticagrelor) to prevent recurrent vascular events.

Stimulating Research: The article points to the need for finding simple and accessible laboratory markers (e.g., within thromboelastometry) to help rapidly identify VAD patients who may not respond to clopidogrel, without the need for complex genetic testing.

Review

For citations:

Popugaev K.A., Kvasnikov A.M., Karpova O.V., Sysoeva A.A., Kruglyakov N.M., Markhulia D.S., Popugaeva O.K. Genetic resistance to antiplatelet agents and delayed stroke development in vertebral artery dissection: a clinical case. Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics. 2025;(2):46-52. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.37489/2588-0527-2025-2-46-52. EDN: JUZAMW